The short answer? They haven't been writing enough

articles like this. For reasons you'll see in a moment, I agree with

Andrew Sullivan that blogs are parasitic on the work of traditional journalists, particularly that of good investigative reporters. But aspects of this situation are changing: bloggers have started to win their fights for press credentials, and the prestige and access that traditional journalists used to enjoy exclusively is starting to look merely overpriced in the face of hard, unique work like FiveThirtyEight's

On The Road series and just about everything original put out by

Talking Points Memo (not to mention larger sites like

The Huffington Post). No longer is it embarrassing to be interviewed by an internet-only publication: as often as not, bloggers are professional journalists who provide information that is utterly lacking in the mainstream, and people have started to realize it.

To make matters infinitely more interesting, some surprising names have started showing up in the bylines on some of the larger blogs:

Keith Olbermann,

John Kerry (who, it turns out, is

awesome),

Ted Kennedy, NY Governor

David Patterson and a number of others all write diaries on Daily Kos;

Darcy Burner and ACORN NYC executive director

Bertha Lewis are now frontpagers on OpenLeft. That's a

fantastic development. To be in direct communication with people in (relative) national power is something that ordinary citizens haven't had a chance to experience since the early 20th century, if ever.

What makes it

so cool are moments like Friday, when Olbermann's post about Clinton's Secretary of State chances was joined on the Kos reclist by a strenuous objection to his reasoning and sources. That is actual, real discourse, and if it hasn't completely unclothed the emperor then it's at least revealing his fairly silly purple underpants.

There's only one truism worth its salt in the Western intellectual tradition, after all, and it was Socrates's fundamental point: no one really knows what they're talking about. There are experts, and there are geniuses, but if you push them hard enough then they'll come up short every single time. And yet, the more you push, the more interesting it gets.

The fact that NYT or CNN reporters are trusted merely because they're in the news is therefore a structural problem with our approach to knowledge. The internet has helped to reveal it, by offering alternatives and forcing improvement, but it's always been there. In part because of that revelation, the traditional media is starting to fail on a number of fronts.

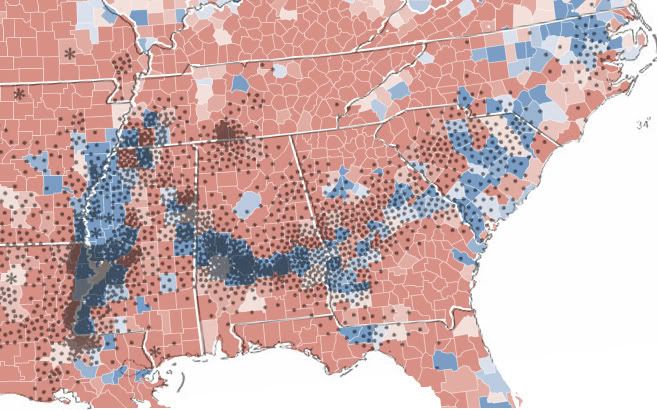

____________________It's not a bad thing, that they're floundering. With all due respect to the incredibly talented people who work in the mainstream – and there are many – the industry as a whole just has no hope of keeping up with the pace of analysis that the average internet user has come to expect. After reading FiveThirtyEight, OpenLeft and Pollster for a month or two, for example, watching someone on CNN talk about their "Poll of Polls", or seeing the AP hype its latest poll without the slightest deference to the surrounding context is downright

embarrassing – and it's a problem that arises because there's no one to tell them to wake up and improve their methods.

To make matters worse, a columnist for the New York Times cannot possibly read and understand every one of the thousands of daily comments. And why should they? Most of them, as far as I can tell, are by crazy people who don't even try to understand the issue. By contrast, the comments on the blogs I read tend to be more manageable and of high enough quality that the solicitation of comments is are often the point of the post. A certain amount of self-selection is a good thing, even if it comes with a price.

As a professor of mine once argued, though, the fracturing of journalism could represent a return to our epistemological condition before the idea of "objectivity" was invented, when trust and knowledge was based more on the individual's personal acquaintance with a speaker than in the norms governing what they said and how they came to conclude it. But that simultaneously short-changes the blogs while over-selling traditional journalism: while the mainstream tends to rely on a small number of relatively static commentators, the internet (at least in its present uncrystallized form) is beautifully meritocratic. Though the actual situation is naturally more complicated, it's not far from the truth to say that bloggers succeed or fail entirely because of their ability while the positions of pundits in other media are determined by a much more roundabout process. (Also, objectivity is made up. But that's another story).

To put it in polemical terms, the internet is more diverse, more open to criticism, smarter, faster, soon to be more heavily populated (if it isn't already). Paradoxically, by contrast, the large media outlets are too small, too limited, too isolated, and too inflexible to partake in the dialogue about current events. Which makes them, in internet terms, too stupid. The small number of traditional news organizations simply cannot offer the depth of analysis of thousands of small blogs.

And there is something absolutely wonderful about the range of news sources today. I'll talk about this in more depth in a later post, but the ability to read five or six articles on a given topic, note their differences and come to an independent conclusion is something that only internet-based media can provide. Once exposed to that diversity, the idea of reading the NYT cover-to-cover everyday seems like just a waste of time. Why trust any one source to get everything about an important story right, anymore?

____________________Yet this is probably a good time to start talking about how we really do need The Press, since newspapers across the country are on the brink of failure (including the vaunted New York Times, whose profits dipped

51% last quarter), posing a real threat to that beautiful diversity.

One of the reasons we need them is theoretical: without national discourse – even stupid national discourse – there's effectively no discourse. We need the stereotypical, largely stupid, sometimes corrupt, constantly maligned mainstream media to say things that we can agree or disagree with. They define the parameters of the debate, because theirs is the largest soapbox. Even if it's sometimes detrimental, they keep us talking about the same things.

But the other, deeper reason we need them is practical. While we may be able to expect a really good blog to reliably post most of the interesting stories of the day, we can't expect any single internet source to have dozens of reporters stationed all over the word. Not yet, anyway: it's an incredibly complex and expensive endeavor to handle the legal challenges and safety concerns posed by international journalism, and blogs aren't up to it yet even though they imply some exciting possibilities. Despite the growth of truly independent news sources, traditional reporters are still the people on the ground for nearly every major story.

That said, the situation facing most freelance journalists today is essentially the same as that facing bloggers. As David Simon repeatedly notes, the cost-cutting measures that newspapers have undergone over the last decade and a half have lead to a general lack of support for investigative reporting (which hits ex-pat reporters particularly hard) and a push to try and win a Pulitzer by presenting the sad but largely bullshit story of a misunderstood community-member. Well, that hurts everyone. I don't care as much if the analysis portion of ceases to exist, since, as I have argued, blogs do it better. But we

need investigative journalism for any of this to work, and that's precisely what's been slipping.

So it's a great relief to see the New York Times putting out more articles like

Secret Order Lets U.S. Raid Al Qaeda by Eric Schmitt and Mark Mazzetti. This is no puff piece. It doesn't begin with a pointless emotive anecdote. It doesn't even provide any analysis. It's just deeply important, meaningful information presented in a clear and factually oriented manner with a sense of narrative flow and of the importance of knowing how important military decisions are actually made. And that's evident from the very first line:

WASHINGTON — The United States military since 2004 has used broad, secret authority to carry out nearly a dozen previously undisclosed attacks against Al Qaeda and other militants in Syria, Pakistan and elsewhere, according to senior American officials.

It's a serious and prescient issue, and so they literally don't waste a single word in the opening. And while there's a

ton of information in the article, enough to give the reader a picture of how the command structure works, it's only about two net-pages long. Really, it's as good an article as I've ever read. It gives me hope for the survival of newspapers, despite the

overwhelming odds.

Of course, it's worth noting that I read it online.